I have always felt conflicted about dedicating myself to creating/building/generating/bringing more items into a world already saturated with everything. As a Fine Arts student, this internal struggle often held me back.

My need to cleanse a world overloaded with information made Gordon Matta-Clark one of my favorite artists. His way of deconstructing and reformulating the urban landscape through cutting and absence became a true obsession for me for a time. Life then took me down much more mundane paths. However, I have continued (and still continue) to be obsessed with eliminating and reducing. Having the opportunity to work on design through visual and conceptual stripping down is not something that happens every day.

However, last week I completed one of those projects that allow for an inward journey and generate experiences, knowledge, and qualitative data, enabling writing and information processing for months.

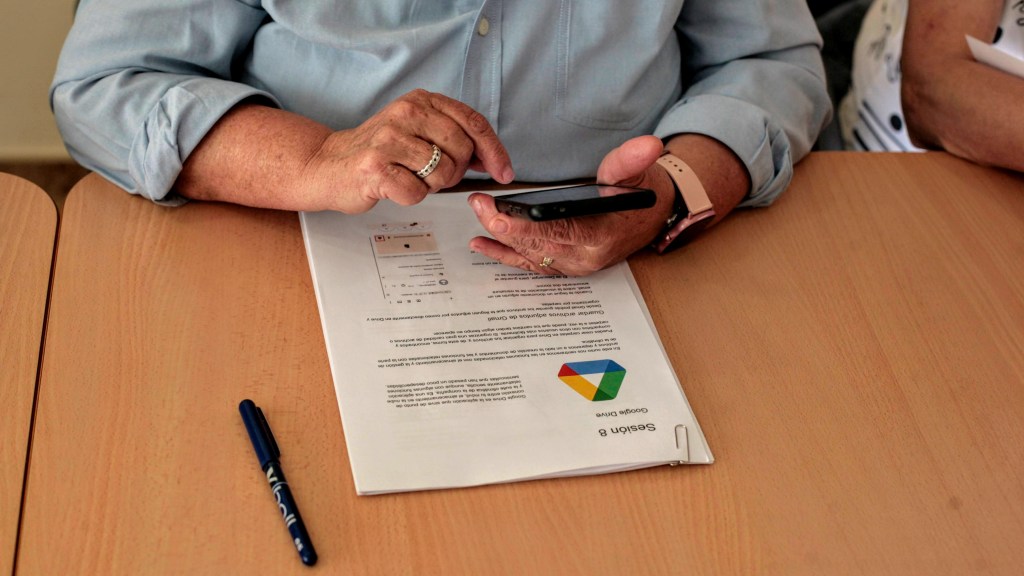

The city council of Fontanars dels Alforins asked me to give a digital literacy course for people over 60 years old, focusing on the use of their smartphones. The request itself was quite vague but had a clear mandate: the attendees should develop skills to become more digitally autonomous.

The starting point was an audience technologically dependent on others for the digital tasks required by basic internet use, usually delegating all their digital information and tasks to the younger people in their close circle: children, nieces and nephews, grandchildren, friends, or neighbors. Sounds familiar, right?

All participants were Android users, and the first question of the course was:

What is the main difference between a smartphone and a conventional mobile phone like the ones you used before having a smartphone?

Or, in other words:

What do you need to start using a smartphone that you didn’t need before?

In response to “a Gmail account,” more than 60% of the participants in the course did not know their own email address, didn’t know where or how to find it, or were unaware they had one. Someone in their circle had set up their phone, and it started working magically. The problem is that if we’re not magicians and we lack training, the magic quickly fades, and the technology in our hands turns into a useless (and quite frustrating) brick.

It’s not a new problem; there are hundreds of courses, articles, and studies on technology and the elderly. After several previous experiences related to design adapted for seniors, my approach was to address it not from an exclusively technological point of view (what can I do?) but from a design perspective (how am I going to do it?), deconstructing for my students different applications that for the average user are already a part of our own virtual brain.

Thus, it was not just about providing training but about conducting a process of analysis and decoding of the design to detect their weaknesses and real threats to use and accessibility. More importantly, it was about identifying where the opportunities lay for this small sample of a target audience that exceeds 9 million people in Spain.

The digital divide that has it all: generational, rural, and gender-based.

According to INE (National Statistics Institute), 94.5% of the population aged 16 to 74 used the Internet frequently in 2023. However, compared to the 99.8% usage found in the 16 to 24 age group, the lowest percentage corresponds to the 65 to 74 age group, which drops to 77.4%.

As the level of education decreases, the percentage of frequent Internet users also declines. In rural areas, these percentages plummet, and the generational gap between young people and those over 60 widens: while 91% of those under 24 have Internet access and 97% use it, for older individuals, only 59.5% have access, and 38.6% use it.

In this case, we are discussing the digital usage gap, setting aside the difficulties many regions may face regarding the digital access gap, as fortunately, we have been working in an environment with good connections.

We’ll focus on mobile devices because they are by far the ones that have managed to introduce the internet massively into rural environments, primarily due to their widespread use compared to basic mobile phones in the mobile phone market, turning the smartphone into the king of rural digitalization.

Elderly individuals have lacked digital socialization. In profiles with higher education, ICT (Information and Communication Technology) was introduced during the latter stage of their careers for strictly professional reasons. The lack of digital education is closely linked to a generally low level of education and, in many cases, also associated with the gender gap. The UNICEF study, What we know about the gender digital divide for girls: A literature review, found that women are 1.6 times more likely than men to self-perceive the lack of skills as a barrier to using the Internet.

Digital emancipation, the primary goal in the training of the senior population.

The main objective of digital literacy for seniors and their inclusion in the digital sphere is to improve their quality of life in old age, regardless of the social contexts in which they operate. Technology should not be a barrier to a fulfilling life, and they should be able to enjoy the advantages it offers at this stage of life.

However, in today’s increasingly complex digital environments, which require continuous and ever faster and more demanding learning, introducing people without any basic technological training from scratch can lead them to almost certain failure. This failure can, at best, result in frustration and abandonment, and at worst, in various degrees of digital scams.

Issues related to privacy and all the information that appears daily in the media regarding artificial intelligence, often sensationalized, generate great anxiety in older individuals, whose learning rhythms vary.

A product’s X-ray is of little use if it’s not accompanied or preceded by an X-ray of the reactions of the person interacting with this product.

La competencia mediática: Propuesta articulada de dimensiones e indicadores. J.Ferrés and A.Piscitelli, 2012

We must learn from the reactions of this population group when designing training tailored to their needs and, why not, also when designing applications that are more accessible, clearer, and more self-explanatory.

Digital design for people over 60: nobody is born knowing.

The main barrier for the senior audience is the lack of knowledge and the resulting distrust. In her study, La brecha digital de género en la experiencia vital de las mujeres mayores, sociologist Gabriela del Valle Gómez, specialized in aging-related issues, points out the following:

Among the identified barriers are some directly linked to the generation, such as difficulties in adapting to software changes and understanding computer language in general. The lack of confidence and personal security is associated with a generational disconnection from the technological environment, which emerges as a new and disconnected universe from usual social practices. Daily life is built around family and proximity relationships, as well as activities that only allow computer use when there is a sufficiently justified need.

When Del Valle talks about “computer language,” she is actually referring to all the elements that concern to design. This includes visual design and user experience design. It’s everything that the user sees and needs to decode to access the information they’re looking for or perform the desired action. Here, I’ve encountered several problems that generate this lack of confidence and completely paralyze users:

They don’t speak English.

They neither speak English nor are familiar with Anglo-Saxon terms that are commonly used on the internet. They are unable to interpret terms as common as “Skip,” “Home,” or “Search,” and therefore cannot navigate out of situations that these buttons could immediately resolve for them.

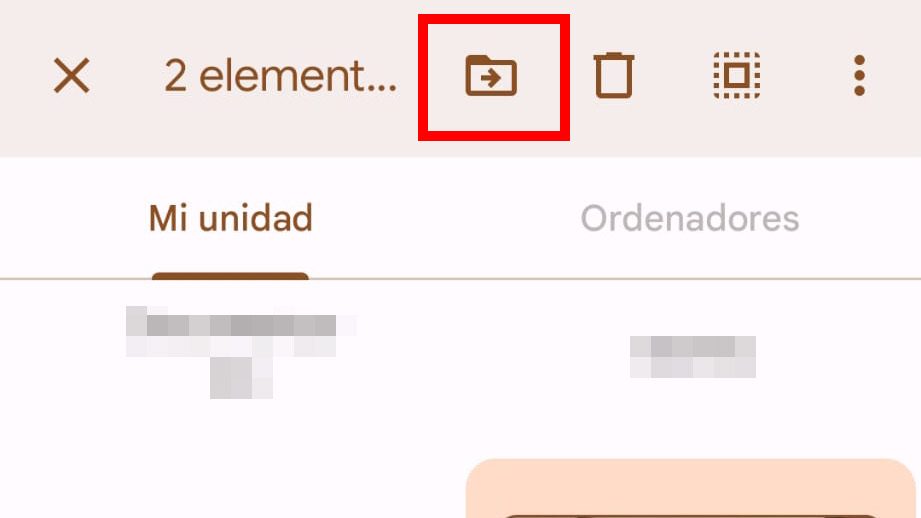

They are not familiar with icons that are standard in design.

Whether they are abstract, like the hamburger menu, dotted menu, or close “X” icons, or figurative, like the house representing “Home” to return to the start or the person icon for “My account” to access profile information, it doesn’t matter.

These visual metaphors, which younger generations have internalized, need to be explained to older users so they can understand and assimilate them. To generate confidence, users need to know both the meaning of the icon and the action triggered by pressing it. They should know what to expect, and above all, understand that it will always be the same (a list of options behind the menu icon, their personal data behind the profile icon, etc.).

Some examples of standards in Google menus that older people find hard to recognize.

They don’t recognize fixed locations.

As experienced users, we would never search for a close “X” icon in the bottom corner of the screen or a Home button in the upper right corner of an app. Our eyes already know where to find each element and ignore places where we know they aren’t when we’re searching for them. This not only provides greater speed but also confidence.

For inexperienced senior users, anything is possible, anywhere on the screen. They need to be told which parts of the screen are divided and what elements they can look for in each location. They need to learn to discriminate between different areas of the screen. And for that, they need to know what happens in each of them.

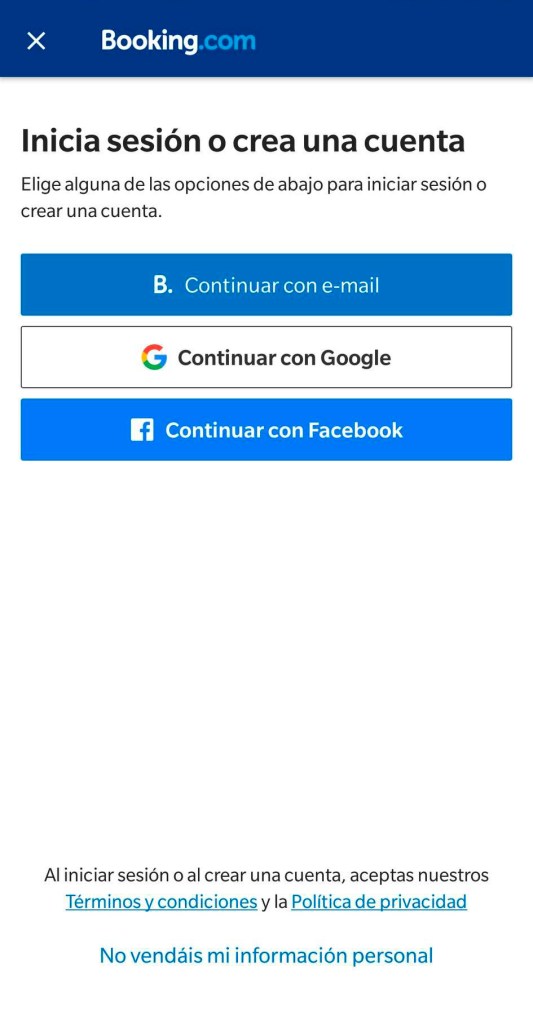

They are perfect victims of any dark pattern

Taking the definition from the AEDP, the term dark patterns refers to user interface designs and implementations aimed at influencing people’s behavior and decisions in their interaction with websites, apps, and social networks, so that they make potentially harmful decisions for the protection of their personal data. The lack of knowledge, lack of trust, and stress generated by managing technology often lead inexperienced users to rush to interact with elements that have been designed precisely to deceptively capture their attention at first glance and thus violate their privacy, if not directly achieve an economic objective. Knowing they are potential victims of these bad practices, which are not illegal, generates a feeling of helplessness that often leads them to give up on technology.

Highlighting options that force registration or sponsored content over search results are dark patterns.

They need support from analog materials.

Due to their learning habits, notes or books are of great help to them. Providing them with printed screenshots, reproducing the sequences of steps they need to take in a registration or search process, gives them greater confidence than recording a tutorial repeating the same process.

Due to their learning habits, notes or books are of great help to them. Providing them with printed screenshots, reproducing the sequences of steps they need to take in a registration or search process, gives them greater confidence than recording a tutorial repeating the same process.

Knowledge will set you free (to say no).

Ignorance and insecurity are ultimately the two barriers that older adults encounter in their relationship with technology. Obviously, we are all vulnerable on the Internet, and anyone can fall victim to fraud. But our ability to defend ourselves and our speed of reaction are key to protecting ourselves, and from this perspective, I proposed the management of all the applications we saw in the course. In general, we emphasized three basic points of security.

- Always keep your passwords well located. We created a paper sheet called a digital will, with 3 columns: service, username, and password.

- Create strong and unique passwords for each service. We defined a best practices guide to use for passwords.

- Activate two-factor authentication on all your services. We reviewed all the services you regularly use, and along the way, we learned how to recover passwords.

Once the best security practices were established, we began to discuss the applications that connect them to the world. We worked on two fronts:

- Applications within the Google ecosystem, beyond those that Android offers by default.

- Applications within the Meta ecosystem: WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram.

Addressing the design systems of Google and Facebook from the perspective of the senior audience is left for another study that deserves to be developed in detail.

Returning to the importance of security and the need to make them feel less vulnerable, the central axis of the course was privacy. One of the objectives, both for the users and the entity promoting the course, was “to learn how to use social networks.” A rather vague objective, especially when we dig a little deeper and ask those who formulate it what use they want to make of social networks.

Facebook and Instagram are the most used social networks in Spain by the population over 60 years old.

What we worked on throughout the course was more about what Meta wants from us versus what it offers us in return. We delved into whether we really need it and if we really want it. We introduced and discussed the attention economy and how this concept has changed the way we manage information in the current world. Of course, we also talked about artificial intelligence and fake news. From there, they began to work on managing their social networks.

Based on the comprehensive privacy and security guides for Facebook and Instagram developed by Xataka, I created a series of educational materials to visualize and locate all (or at least as many as possible) privacy options on both platforms. We also went to the other side of the Meta Business Suite panel and saw how these platforms allow advertisers to manage ads, how they segment the audience based on the information we provide, and how they return that information to us in the form of ads and suggestions.

We worked from the worn-out idea that “if something is free on the Internet, it’s because you’re the product,” which, although cliché, remains true, and we learned to develop protection strategies. With this knowledge, everyone decided whether or not to use the networks and to what extent. But always well-prepared and knowing how to take maximum precautions possible.

Keep calm and take control

Although I’ve been compiling notes in the form of a small “textbook” with materials tailored to their needs throughout all the sessions, I’ve attempted to summarize the course into a few basic tips that are easy to remember and I believe can be greatly beneficial to anyone inexperienced in technology usage, particularly, as in this case, with smartphone usage:

1. Read everything

Before doing anything, before feeling overwhelmed by the screen, take a breath and read everything that is written. Most likely, by reading calmly, you will clearly see what the next step should be to achieve your goal on a website or in an application.

2. If you’re unsure, don’t accept

If you’re unsure, read again and reject anything that isn’t 100% clear to you. No digital product can force you to accept terms that you’re not interested in. In the case of cookies, you can reject them or browse incognito to minimize their impact. Regarding app permissions, remember that apps can function without many of the permissions they request, and if you make a mistake and accept something you didn’t want, you can always reverse the permission. On the contrary, if you deny a permission that is necessary for the optimal functioning of the app, it’s also okay because when you try to use it and the app can’t, it will ask you again and send you to the Settings screen where you need to activate it.

3. You can always Go back or Close

If you’re unsure of where you are, always look for the arrow pointing to the left (Go back) or the Close “X”. Surely, somewhere on the screen, one of these two icons is present. With them, you can return to the previous screen or start over with the action you wanted to carry out.

4. Look for the icons you recognize

If you can’t find these two icons, look for any of the standard icons you know (Home = House, 3 lines or 3 dots = Menu, Person icon = My Account) and try to reach your goal through these options.

5. Use the search function

If you can’t find what you’re looking for, look for the magnifying glass icon. Next to it, you’ll always have a text field where you can click and type what you’re searching for. If what you’re looking for exists within the app or website, the magnifying glass will show you how to get to it.

6. If you can’t do anything else, exit the application

If you’re truly lost, close the application using one of the device’s three main buttons. Then reopen the app and try again.

Digital literacy as a collective challenge

No one should feel excluded from the system due to lack of knowledge. This obvious fact, on which we can all agree, seems not to be so evident in the realm of technology and aging. Most of the time, we assume that our elders are incapable of integrating into the communication model we handle, which requires continuous learning and the activation of certain mental reflexes that even those of us who work in this field sometimes find overwhelming and exhausting. However, having difficulty sending a location via WhatsApp or managing email should not equate to abandonment.

Technology has much to offer our elders. It can make their lives easier, more bearable. It can alleviate their loneliness, connect them with distant relatives, and bring them closer to the places of their childhood where they can no longer physically travel. It can serve to leave us with a testament, written in the form of a blog or oral in the form of a video, of a disappearing world, which some of us perceive as shrouded in mist and which future generations know nothing about.

It is our obligation as a society to promote spaces for digital integration and learning for our elders. It is our obligation to adapt to their rhythms, which teach us other ways of proceeding, also with technology. Other ways of addressing design problems and defining processes. Ways of working and looking at the technology that comes our way. It’s about accessibility, but it’s also about going beyond that. Not just finding a way for them to adapt to the system. The system must be able to learn from their processes. Because generations will pass, technologies will change, and we will become them. We will lose reflexes, we will find it difficult to learn at the frenetic pace that the world sets at any given moment. We will want the system to look at us and seek ways to integrate us, not to leave us out because our abilities and ways of doing things are different.

Let’s learn from people again. After all, that’s what AI does: learns from what already exists. Let’s learn too. In a landscape where we all fear that artificial intelligence will take over our jobs, it would make more sense to turn towards people than to try to compete with machines. There is much to learn from human processes that seem not to be observed or monitored with the same interest as others (perhaps because they are not economically as profitable). And we cannot afford to overlook the opportunities that technology offers us when we change the direction of our gaze.

Leave a comment